College Students Invent Gloves That Translate American Sign Language

[:en]

Just when I thought I saw it all, SignAloud came along. An invention that truly fits its namesake, SignAloud is a pair of gloves that translates the physical gestures of American Sign Language into audible English. Science fiction has become science reality as this inclusive technology enables members of the Deaf community to communicate with hearing-abled individuals by utilizing their own fluent form of speech.

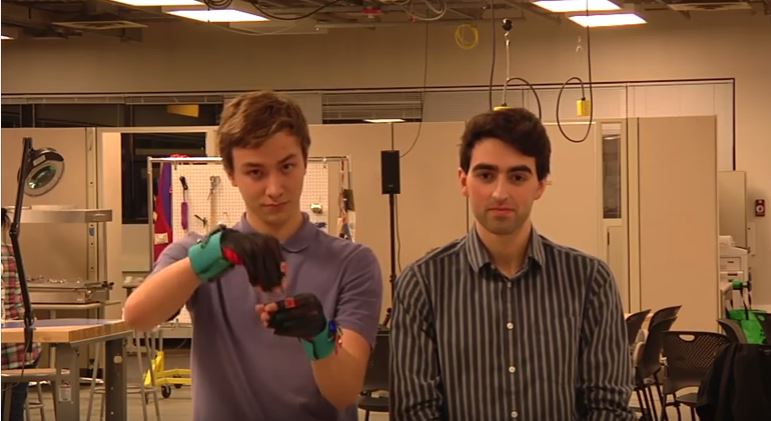

This remarkable innovation was developed by University of Washington students Navid Azodi and Thomas Pryor.

Check out how it works!

The two sophomore inventors are winners of the Lemelson-MIT Student Prize, which honors promising collegiate inventors around the country who have developed inventions in categories that represent significant sectors of the economy, including healthcare, transportation, agriculture or consumer devices. In addition to top media coverage and what I would imagine to be a surging popularity on their Seattle campus, the two sophomores received $10,000 from Lemelson-MIT.

While this isn’t the first invention to tackle sign translation, it is certainly one of the few that takes into account the everyday behavior of the user. One of the main factors that separates SignAloud from previous iterations and competing devices is its inconspicuous nature. Describing the viability of the design, Pryor told UW Today, “Many of the sign language translation devices already out there are not practical for everyday use. Some use video input, while others have sensors that cover the user’s entire arm or body. Our gloves are lightweight, compact and worn on the hands, but ergonomic enough to use as an everyday accessory, similar to hearing aids or contact lenses.”

The combination of technology and design is being more widely appreciated in recent years, as companies and developers recognize that a device’s value and commercial success- even when it comes to disability-focused innovation- is not solely dependent on “does this fix the problem,” in this case, allowing people who are deaf to communicate with those who are not deaf. Because of the competitive marketplace, that problem-solving need now fully extends to the functional: its ease of use, comfort, brand (cool factor) and ultimately, how it makes the user feel.

“Our purpose for developing these gloves was to provide an easy-to-use bridge between native speakers of American Sign Language and the rest of the world,” Azodi said to UW Today. “The idea initially came out of our shared interest in invention and problem solving. But coupling it with our belief that communication is a fundamental human right, we set out to make it more accessible to a larger audience.”

The communication barriers that this invention minimizes are a good reminder of the social model of disability. Our society often tends to think of disability as a medical “deficiency,” but we see over and over again that when we create accessible environments and adaptive technologies—in other words, when we change our surroundings rather than individual people—disability is no longer an impairment. After all, I believe that full inclusion, just like communication, is a human right.

On that note, I have to point out one aspect of these amazing gloves that are a barrier to full inclusion: what if the person signing cannot read lips. The gloves create a one-way stream of communication that does not take into account an issue many overlook or do not know exists. According to Johns Hopkins University Office of Student Disability Services, only 30 to 40 percent of spoken English is distinguishable on the mouth and lips under the best of conditions. I hope that Azodi and Pryor and other innovators will soon develop a device that is equally well-designed and allows for those who do not speak sign language to communicate seamlessly with those who do.[:]

About the author Kristina Kopić, better known as Tina, is a former academic, a writer, a martial artist, and a fan of deconstructing all social constructs, especially those of gender, race, and disability in order to expose and challenge their injustices and create a more inclusive and fair world. She is the Advocacy Content Specialist at the Ruderman Family Foundation, lives with her wife, their two cats, and is currently dabbling in rugby.

Stay Included

To stay up to date on our most recent advocacy efforts, events and exciting developments, subscribe to our newsletter and blog!