When Limbs Aren’t Missing—The Future of Orthotics

If I asked you what comes to mind when you think of orthotics, you would probably think of shoe inserts, and you wouldn’t be alone. While that’s the most widespread use of the word, an orthosis is actually any device that, when worn, impacts the function of your muscles, joints and/or skeleton—in other words: braces. Knee braces, wrist braces, neck braces etc. are all orthoses. It’s indisputable that all our lives would at some point be harder without these gadgets, but I suspect that even the sleekest ankle brace won’t capture your imagination. So now that we’re on the same page of what an orthosis is, forget the braces and instead think Iron Man and RoboCop.

“Like RoboCop, but not bulky,” said Dr. Richard Rome when we spoke about his latest research on the front lines of orthotics development at the University of Texas at Dallas. The most recent advancements in this field are quickly approaching sci-fi levels and Rome generously shared a bit of his lab’s progress with me; the more important why behind his work, but also the how.

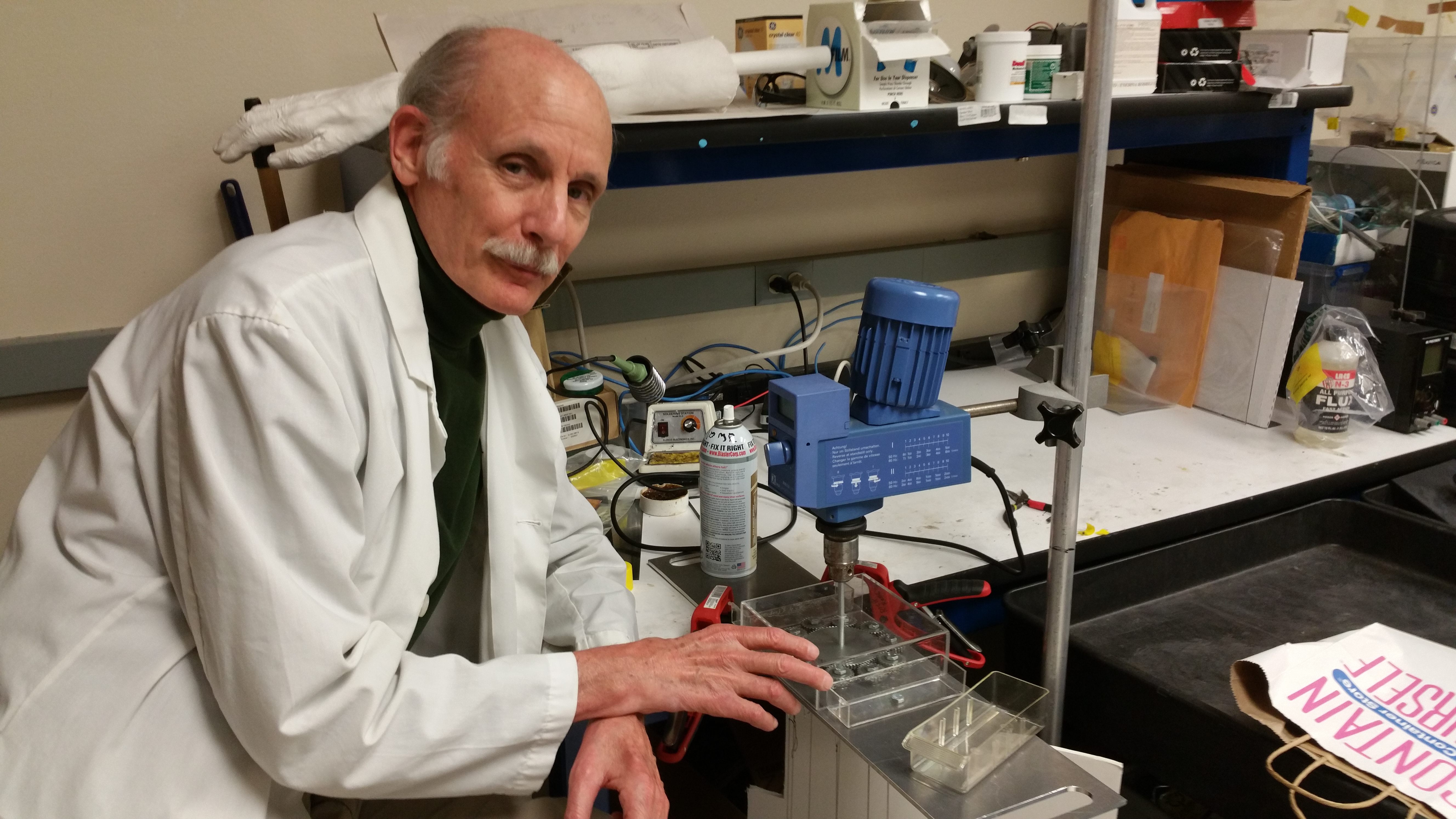

Richard Rome, MD, working with his machine which creates polymer fiber “muscles.” (photo credit: Richard Rome)

It is hard to find an exact number of people who have some form of neuromuscular disorder, like ALS/Lou Gehrig’s disease, Huntington’s disease, or muscular dystrophies. The National Multiple Sclerosis Society estimates that there are around 2.3 million people worldwide who have multiple sclerosis and based on the estimates for other neuromuscular disorders we are looking at a few more million people whose illness leaves them with varying degrees of immobility. If you add to that people like myself who through injury are temporarily unable to use their muscles (I dislocated my shoulder in a sports accident and was unable to use my arm for several months while my nerves regenerated), you are now looking at tens to hundreds of millions of people worldwide. Put this way, the need for orthoses becomes very clear.

However, “the truth of the matter is that people who have intact limbs have not received attention from research that amputees have. The military funds prosthetics for returning vets,” said Rome, but there is comparably little funding for devices that would help people who are losing the use of their limbs while they still have those limbs. This is where Rome’s research comes in. He is a retired radiologist and nuclear medicine physician and while he still practices radiology part time in Laredo, Texas, a lot of his focus goes to his orthotics work at the University of Texas. He himself has Charcot-Marie-Tooth 2F (CMT), a rare genetic disease that impacts skeletal muscle. The symptoms start manifesting through a weakening of the leg muscles and progress to the center of the body. “I am the first person with it in four traceable generations. I must have been a spontaneous mutation,” Rome said, explaining that it is a genetically dominant disease. “I realized a long time ago that anything I could do to improve my prospects, improves others’ prospects, too.” And his work stands to truly improve the prospects of many.

Because Rome’s research isn’t published yet, he wasn’t able to give me too many details, but suffice it to say that the basic outline is utterly fascinating. In short, Rome has built a machine that helps him create artificial muscle fibers. His lab used to make them with “expensive, very sophisticated carbon nanotubes” until a very smart grad student, as Rome put it, brought up a piece of information that had been known since the discovery of nylon in the 1930s. Namely that if they made their muscle of nylon fiber—fishing line really—“they are 64 times more powerful on a weight basis than skeletal muscle.” And this brings us back to the less bulky RoboCop. Imagine wearing a garment that augments your natural muscle strength so that even if your muscles are not working due to disease or injury, you are still able to do basic, daily tasks.

“We’re addressing activities of daily living,” Rome said, “brushing teeth, holding cups, brushing hair, maybe writing. … We have to analyze all the muscle action that goes into each activity we want to reproduce and reduce those muscle contractions to a computer program, so that the computer can then say ‘oh, it wants me to grab’.” I was quite literally sitting on the edge of my seat during this conversation. I may have even gotten up and began pacing because the thought that this kind of orthotic would exist not in sci-fi films, but in the present was blowing my mind. But the big question is how exactly do you tell a computerized piece of clothing that you want it to move your arm and grab a cup of water?

The University of Texas at Dallas is not a medical center which means they don’t get direct access to patients. “Johns Hopkins do have access, so they’re implanting electrodes in the cortex of the brain to work prostheses through a computer,” said Rome. Instead his lab goes through a “series of approaches that start with a patient who is alert and awake and has some function on one side opposite a stroke or a patient who can speak into cell phone that has voice recognition.” With these non-invasive methods, patients can command their orthoses, similar to how Stephen Hawking commands his synthetic voice.

Rome’s lab is applying for multiple grants to continue to fund their research, including a National Institute of Health grant. So when could we expect to see this promising technology that could significantly improve so many lives? “Three years, ready for market,” Rome said. “That’s a true statement.” Welcome to the future.

About the author Kristina Kopić, better known as Tina, is a former academic, a writer, a martial artist, and a fan of deconstructing all social constructs, especially those of gender, race, and disability in order to expose and challenge their injustices and create a more inclusive and fair world. She is the Advocacy Content Specialist at the Ruderman Family Foundation, lives with her wife, their two cats, and is currently dabbling in rugby.

Stay Included

To stay up to date on our most recent advocacy efforts, events and exciting developments, subscribe to our newsletter and blog!